Drink in the Glass

page 19 >>

Control of the Use of Alcohol

‘Ye’ll hae a wee dram’

Laws relating to the control of drink are at least as numerous as those which affect the production, distribution and consumption of food. Fortunately it is beyond the interest and scope of the present study to dwell upon the detail of either set of lawsa. No gastronomic history which includes the question of drink in Scotland can ignore the question of social control and it is the purpose of the present section to show where the later discussion will lead. A whole sociology of drink opens up with ‘You will have a wee dram?’ and the invitation has wide understanding in the English-speaking world beyond Scotland. It can mean ‘you will have one otherwise I will be upset’ and thus a basic rule of etiquette, to accept hospitality when offered, is broken if the answer is no. It also implies that it will be more than the absolute minimum which might be offered and accepted. We will explore the idea of whisky as ‘the language of hospitality’ in Scotland in Chapter 6: The Inordinate Love of Whisky.

This emphasises the importance of the use of alcohol and if we are to look at it in Scottish society in the past an idea of the cultural overtones would be useful.

“Qui feut premier, soif ou beuverye? (What was first, thirst or drinking?)”9

The ingestion of certain fluids is often unrelated to actual bodily requirement and culture interferes with the demand mechanism.

“The virtues of alcohol have been discovered independently by many peoples, and they have found many ways of producing the alcohol: through allowing the sweet sap of palms and other plants to ferment, through fermenting grains or fruits, through chewing starches (like manioc) and fermenting the saliva-mixed product. And primitive man ransacked the plant kingdom to find substances that could be drunk, chewed or inhaled for a lift, or for a temporary escape into the world of dreams.

“These ‘perversities’ may be accepted and institutionalised by the culture, or they may be suppressed or hidden or deplored… “109

The acceptance of a particular product is to include it in the food-ways of a culture. The rejection of another product, albeit accepted by foreigners perhaps is to allocate it taboo status. Decisions are made, as Bates would concur, in the cultural context. The suppressions and hidings are deplored not only in the way people behave towards the alcoholic but in the drink law of the land which we can look at later.

The interactive elements of social control have been intimated in looking at the ‘wee dram’. It was the view of Shibutani11 that “’Social control’ refers not so much to deliberate influence or to coercion but to the fact that each person generally takes into account the expectations that he imputes to other people.” The consequence of not taking into account such imputed expectations is that entry to, or continuation within that stratum of society is not permitted. While there is no compulsion to join the other in a drink in Scotland (this was not true in previous times when we consider the detail provided by Dunlop12) possibly more than elsewhere the pressure to accept the token of hospitality (to be discussed) can be an embarrassment to the teetotaller. The social custom is taken for granted until refused.

“In some cultures alcoholic beverages are an accompaniment to most meals, in others they are a social custom, and in some they are used for their euphoric effects … An individual may drink because it has been a family custom since his childhood, because he seeks euphoria to blot out a miserable existence, because he can use it as a masked method of self-distinction, because it is a social custom at parties, because it relaxes him.”13 It would be somewhat arbitrary to decide that the use of alcohol in Scotland falls within one of Bischoff’s categories. Clearly it is a social custom, the presence of food is not a condition for its consumption but the euphoria dimension is important especially when we reflect upon the extent of general poverty in Scottish history and the obvious sacrifices which must have been made in order to make it on the hillside using ‘valuable’ grain or buying it in the city.

Still looking at drink in general terms we find that there are many dimensions and Ayer saw the act of “… raising a glass … and drinking it” as:

“… an act of self indulgence, an expression of politeness, a proof of alcoholism, a manifestation of loyalty, a gesture of despair, an attempt at suicide, the performance of a social rite, a religious communication, an attempt to seduce or corrupt another person, the sealing of a bargain, a display of professional challenge …”14

We have no need to explore each of these facets but there are a few deserving of special attention. Thus we will have concern for “… the performance of a social rite”, “the sealing of a bargain” is covered in the Dunlop debate and we can extend the idea of whisky (etc) as the

“language of hospitality” in considering Ayer’s “expression of politeness.”

Patrick15 was another to reflect upon the various cultural uses to which alcohol is put and gives wine as an example. “By social definition it may have none, one or all of the following uses in a particular society: a symbol for the blood of Christ at a communion service, a condiment or beverage with meals, a method by which heightened fun and enthusiasm may be produced at a social gathering; or a narcotic to enable people to escape, at least for a while, certain disagreeable life situations.” Perhaps the “disagreeable life situations” are created by general social control from which the drinker hopes to escape.

There are, however, numerous situations where alcohol is a significant component and social control is concerned with every individual learning the rules surrounding its use. These rules vary; some prevail across the whole population in terms of laws while others are relevant to groups of people in a more informal but nevertheless prescriptive way.

It is not the purpose of this discussion to prove that Scottish drinking habits are worse than those elsewhere, rather to show the social context in earlier times. “For it has been taught in the bosom of the family, by the father’s example and by the mother’s precept that wine, beer and spirits are useful, nay, necessary to health, and that they augment the strength. And the lessons thus indicated and too well learned have proved to be the steps which lead to wider experience in the pursuit of health and strength by larger use of the same means.”16 Here we see an expectation for the plentiful use of alcohol as a source of physical energy and health – the more one drinks the

healthier one becomes!

...

20

A 1935 view of an aspect of Welsh drinking is here http://www.jstor.org/pss/2789906 and is an arbitrary first link.

page 21 >>

Temperance and Legal Controls

The next stage of the discussion relating to the social control of drink is to consider the forces against its use in Scotland in former times. The legal constraints have virtually always been present in some form or another. The Temperance movement arose out of the lack of effect of such laws and endeavoured to increase their severity as well as perhaps attempting to be to the drunken community what the Improvers hoped to be to the agricultural community.

The President of the General Temperance Movement of Scotland in the mid nineteenth century was John Dunlop and his main work is deemed to be of sufficient importance to be summarised later19. Surprisingly, there is nothing specific to the following debate beyond that which is included in the summary. The effect which temperance societies had on earlier patterns of Scottish drinking is difficult to assess. MacNish20 saw that “They have been represented by their friends as powerful engines for effecting a total reformation from drunkenness.” To this day there has been no such reformation.

An early indication that Scotland had a drinking problem is noted by Chambers. On May 28, 1625, “The town-council of Aberdeen … anticipated the wisdom and good manners of a later age by ordaining that: ‘no person should, at any public or private meeting, presume to compel his neighbour, at table with him, to drink more wine or beer than what he pleased, under the penalty of forty pounds’”21. In the subsequent years laws became national and “Temperance legislation, in its mildest form, may be said to date from the Home-Drummond Act of 1828 which conferred on Justices of the Peace “… the granting of certificates for the sale of liquor … Twenty-five years later, in 1853, the Forbes MacKenzie Act reduced the hours of sale (8am to 11pm), closed the public-houses on Sundays, prohibited the sale of drinks in toll-houses situated within six miles of a licensed house, and restricted the licensed grocer to selling drink for consumption off the premises only.”22 We shall have more to say about Forbes MacKenzie soon.

The “Tippling Act23 came into force in 1750 in order “to protect the poor from unfair temptation and fraudulent demands” in relation to being given credit and the subsequent request for settlement.” This had arisen from the extensive amount of drinking in the first half of the

eighteenth century. Other legislation followed: Sale of Spirits Act, 186224, County Courts Act Amendment Act, 186725. (Bar credit, however, was still being provided as late as 1914. Section 8 of the Licensing Act, 192126 may have been the main breaker of ‘the slate’).

In 1834 a Select Committee of the House of Commons was set up “to enquire into the extent and causes and consequences of the prevailing intemperance among the labouring classes of the United Kingdom”. It was chaired by James Silk Buckingham and included such men as Sir Robert Peel and Lord Althorp. Space restrictions permit only a mention of the ‘fact’ that “… the vice of intoxication has been for some years past on the decline in the higher and middle ranks of society” 27. The focus was “the labouring classes” who were still apt to use “the many customs and courtesies still retained from a remote ancestry of mingling the gift or use of intoxicating drinks with almost every important event in life, such as the celebration of baptisms, marriages and funerals, anniversaries, holidays and festivals, as well as in the daily interchange of convivial entertainment and even in commercial transactions of purchase and sale.”28

Temperance in Wales - a start to the research

"By the beginning of the nineteenth century heavy drinking was common in Wales. The situation deteriorated in 1830 when the Beer Law was passed that allowed any taxpayer who paid two guineas a year to open a beer house. This led to a significant increase in the number of public houses, especially in the towns and industrial areas."

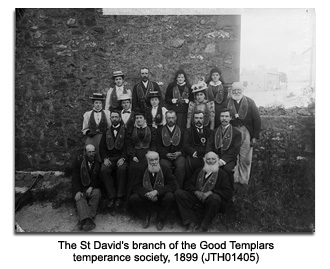

The quotation and photo is from http://www.llgc.org.uk/index.php?id=temperancenlwms8323b

- Home

- A Preliminary

- Increased use of libraries

- A COMMUNITY PROJECT

- The project public face

- The Project Originator

- Who can be involved

- Project resources

- INTRODUCING THE HAGGIS

- Unsatisfactory Diet

- Welsh National Gastronomy

- Structure

- FROM THE HAGGIS BOOK

- More than Oatmeal

- Carbohydrate

- Meat on the Plate

- Drink in the Glass

- At the Pub

- Control

- Self-identity

- MORE ON RESOURCES

- Haggis etext

- Are We Really - etext

- Green Gastronomy

- Gastronomy introduction

- New Gourmet Society for S E Wales

- Another Resource for you

- CONTACT

- The last word